Announcements

The College of Wooster’s Stieglitz Memorial Lecture is on Monday (2/12) at 7:30pm in Lean Lecture. The title of the lecture this year is called “White Bound: Nationalists, Antiracists, and the Shared Meaning of Race” by Matthew Hughey, a professor from the University of Connecticut.

A blog post is due on Friday (2/16) proposing a potential article that you can edit for the Wikipedia Article assignment, so it would be beneficial to start thinking about what topic interests you sooner rather than later.

Culture Blog Post

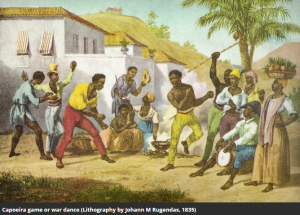

Woo did his culture blog post on an article in the Smithsonian about Capoeira, an Afro-Brazilian martial art that is mixed with dance elements. Woo specifically talked about how the Capoeira has transformed over the years. In the 16th century, Capoeira was only done among enslaved Africans in Brazil to practice defensive attacks so that they could resist European oppression. By late 19th century, the freed slave population moved to urban areas and continued to practice Capoeira for defensive purposes. However, in the 20th century, Capoeira was promoted more as an art form and elites began to support it as well, which allowed it to become the official national sport in 1972. Woo also looked at the portrayal of Capoeira in a video game called Tekken to see how Capoeira plays a role in national identity. Overall, Woo tied this article with the class theme of Brazilian diversity and how Brazilians seek to maintain a culture of their own.

The Day’s Activities

Exploring Primary Sources

After the culture presentation, the class focused on the topic of abolition in Brazil. The specific questions the class took into consideration included: If African slavery was so important in Brazil, how do we explain its abolition? What kinds of sources exist for analyzing slavery and abolition and how do our choices shape the argument we make about the past? In order to tackle the first question, we turned to some primary sources we had for homework from the Brazilian Reader and additional primary sources from Professor Holt. One primary source that we talked about in class was Nabuco’s passage called “Slavery & Society”. Nabuco came from an elite sugar plantation family and was the son of a politician who hated slavery. Thus, Nabuco himself became a famous abolitionist during the 19th century in Brazil. In this passage, Nabuco makes the moral argument against slavery. He claims that slavery has a detrimental effect on Brazil as it morally corrupts society as a whole. Specifically, slavery acts as a huge obstacle to the civilization of Brazil. Nabuco calls Brazilian society hypocritical for tolerating slavery and believes that Brazil is not truly independent until slavery is abolished. The Nabuco primary source allows us to answer how slavery was abolished in Brazil despite its importance in society. Looking at this source only, it can be assumed that slavery was abolished to further civilize society in Brazil, as the social consequences of slavery outweighed the economic benefits. However, by looking at more primary sources, we can get a more complete answer to this question.

Next, we looked at a primary source from Princess Isabel, specifically her final decree of abolition, officially named, “Abolition Decree, 1888.” In the decree, Princess Isabel abolished all slavery and revoked all other laws that stated otherwise. This decree itself abolished slavery, which highlighted the power of the royal family in Brazil at the time. This primary source helped us answer our initial question by considering the power of the elites, specifically the royal family. The other primary source we looked at that was not assigned for homework was a painting called “The Freeing of Slaves” by Pedro Americo in 1889. The painting depicted white people as angels, with the majority of people being women. The white people were all nicely clothed, while the slaves in the painting were naked and depicted as pitiful. This painting depicted abolition as a white gift to black people and, again, suggests that slavery was only abolished because of the elites.

“The Freeing of Slaves” by Pedro Americo in 1889

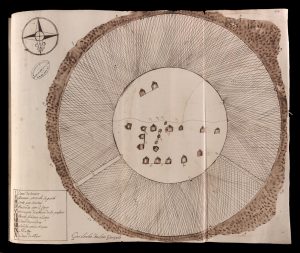

However, this was not true. The next primary source was a map of the Sao Gancalo Quilombo Minas Gerais from the late 18th century. The fact that the government contained a map of a quilombo hints that the colonial state felt anxious about a possible slave revolt, which suggests that enslaved blacks did try to fight for their freedom and did not just wait for the elites to abolish slavery. This idea was reaffirmed with the next primary source, which was a book confiscated from slaves who attempted to revolt in the Male Revolt in Salvador, Bahia in 1835. This book was worn around the neck and was written in Arabic. This suggests that people planning the revolt were literate and multilingual. It also shows another element to the abolition struggle: possible cooperation between the enslaved and freed.

Map of the Sao Gancalo Quilombo Minas Gerais from the late 18th century

Discussion on Camillia Cowling’s “Debating Womanhood, Defining Freedom: The Abolition of Slavery in 1880s Rio de Janeiro”

After analyzing these primary sources, the class broke into small groups to discuss questions pertaining to the Cowling reading, a secondary source. The questions considered included, What kinds of sources does Cowling use? What is the main argument? How does her research complicate our understanding of slavery and abolition in Brazil? Why is this important? Cowling uses a variety of sources, including letters from slaves, council records, laws, and newspaper articles. Her main argument is that gender and abolition are very connected and that maternalism played a big role in abolition. Overall, she argues that women played a large role in the abolition movement in Brazil, which is often overlooked. Her argument and research complicates our understanding of slavery and abolition in Brazil as the roles of slaves, particularly women, is often not considered in the abolition processes within other countries. Usually, abolition movements are thought of as an elite-led movement, but in Brazil, it is viewed as a legal battle led by enslaved women. This is important to consider when looking at different abolition movements, such as how Brazil was able to minimize violence opposed to the war that broke out in the United States.

By looking at all these primary sources and the informative secondary source, it is clear that one must read many different perspectives on a topic in order to have a more complete understanding of a situation. For example, if we only looked at the primary sources from elites, we would have thought that abolition was an elite led movement. However, by looking at primary sources from slaves and government records as well as the Cowling secondary source, we get a more complete understanding of how the abolition movement work, specifically the huge role enslaved women had.

Key Terms

Quilombo: settlement of runaway slaves

Pano: a headwrap Brazilian women would wear

Christianity: believers in Jesus

Protestant: Christian, but fundamentally different than Catholics due to its emphasis on the bible

Catholics: earliest Christians that are sacrament based, which most Brazilians were in the 16th, 17th, 18th, and 20th centuries.

Links

https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-slavery/chronology-who-banned-slavery-when-idUSL1561464920070322 This website gives a timeline on how slavery and abolition played out in Brazil.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2518384?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents An article providing an overview of the causes of abolition, including humatarian pressure.

https://www.britannica.com/event/Rio-Branco-Law Gives an overview of the Free Womb Law and the background on how the law was titled.

Possible Exam Questions

How did women play a role in abolition and how did maternalism play a role as well?

Although the Abolition decrees was passed in 1888, how were freed slaves treated after abolition?

Who were all the actors involved in abolition and how did their efforts intertwine to accomplish the goal of abolition?