Attempted Prison Break Leaves 21 Dead in Brazil’s Amazon Region

This article, published in the Rio Times, discusses a recent incident in which the Santa Izabel Prison Complex, a Brazilian prison, was assaulted from the outside. The attackers, described only as “a heavily armed group,” used an explosive device to blast through a wall and “facilitate the escape of inmates” (Alves 2018). In a subsequent investigation by the Para state Department of Security and Social Defense, an indeterminate number of the prisoners themselves were found to have been in possession of weapons at the time of the offensive. A total of twenty-one people ultimately lost their lives over the course of this event, including a prison guard, five inmates attempting to escape, and fifteen individuals working to free the prisoners (Ibid.).

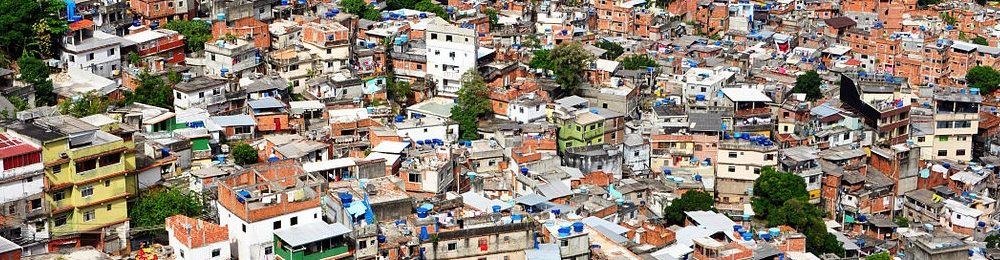

Santa Izabel is located near Belem, Para, a state capital in the Amazon river basin. In February, the National Council of Justice had warned both state and prison officials of the high probability that there would be a large-scale escape effort in the near future. Moreover, the agency had recommended the construction of an additional wall and an enhanced security presence around the particular compound which would be breached two months later. This facility, the Center for Recovery of Penitentiary Para III, was found by the Superintendence of the Penitentiary System to be capable of housing no more than 432 prisoners. However, at the time of the jailbreak its cells were well over capacity, holding “a total of 605 inmates” (Ibid.).

Upon observing the broader Brazilian prison system, one finds that this instance of violence, overcrowding, and apparent negligence by public servants is not unique to the complex in Para. Writing for the American University International Law Review, Layla Medina finds that the country regularly fails to enforce its own laws on the treatment of inmates, in addition to passively condoning actions which violate the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Through her research, the author also determines one of the key factors behind all of these problems to be the criminal justice system’s pervasive failure “to grant detainees a prompt custody hearing,” which in turn leads to overcrowding and leaves prisoners vulnerable to abuse by guards and other inmates (Medina 2016, 627). These problems are further exacerbated by significant political pressure to impose harsher punishments for relatively minor offenses, which disproportionately impacts poor communities and ensures that prison populations expand faster than the facilities accommodating them (Ibid., 612-27). It can then be stated that the problems highlighted in these articles are deeply connected to the social and economic divisions that have plagued Brazil since its independence, and will likely persist until such inequalities are recognized and properly addressed.

Works Cited:

Alves, Lise. “Attempted Prison Break Leaves 21 Dead in Brazilian Amazon Region.” Rio Times, April 11, 2018. http://riotimesonline.com/brazil-news/rio-politics/attempted-prison-break-leaves-21-dead-in-brazils-amazon-region/.

Medina, Layla. “Indefinite Detention, Deadly Conditions: How Brazil’s Notorious Criminal Justice System Violates the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.” American University International Law Review 31, No. 4 (July 2016): 593-627. http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr/vol31/iss4/3.